By Verah Okeyo and Salome Bukachi

One Health research that examines the health of people, animals, and ecosystems using a gender framework is likely to offer more benefits to at risk communities compared to disease management approaches that ignore gender dynamics. This is because the threats and severity of disease epidemics affect people differently.

A critical aspect of how people live includes norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships between genders which vary across cultures, are dynamic and can produce inequalities. Yet these dynamics are sometimes ignored and in health research design and conduct.

“Even though One Health research is multidisciplinary, it does not always incorporate gender from the start. This is because research is influenced by policies, which also influence how people live,’ said Salome Bukachi, professor of Anthropology at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, at a recent COHESA webinar.

At a webinar, held in June 2024, ILRI’s gender researcher, Zoë Campbell, explained how gender can be integrated in One Health research using a new framework. Using a One Health research case study in Uganda that focused on pork tapeworm (Taenia solium), a zoonotic parasite that causes illness in people and pigs, Campbell explained how a person’s gender roles within their household or community can affect their vulnerability to disease caused by pork tapeworm. She described how gender dynamics can be considered in proposed interventions to address health issues and suggested the following steps.

Step 1: Recognize the importance of gender

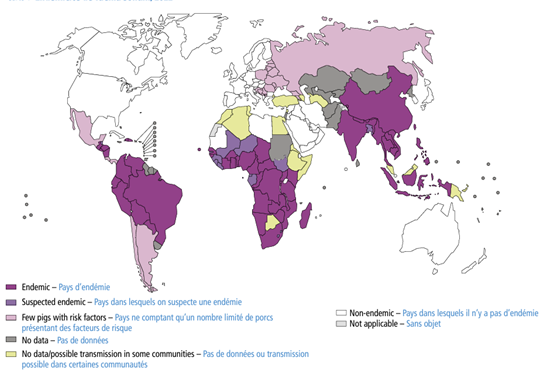

Taenia solium is present in nearly one in four countries in the world. It is endemic in 51 countries but the disease is treatable with anthelmintics and anti-parasite drugs such as praziquantel or albendazole.

Endemicity of Taenia Solium. Source: World Health Organisation

Hygiene and proper cooking of pork can prevent pork tapeworm infection. But the adoption of these measures it is not simple because, as Campbell said, ‘gender and other markers, such as age, dictate behavioural norms that influence men's and women’s everyday actions, expectations and experiences.’ For example, the researchers found that women in Northern Uganda may avoid latrines due to a belief that if they use them, they will never bear children.

Campbell recommended the inclusion of gender researchers in multidisciplinary One Health research teams. These may include men and women gender specialists, epidemiologists, veterinarians, and people from other scientific disciplines.

Step 2: Include gender in the research design

The pork tapeworm case study research team included a gender component early on when the potential study sites in Northern Uganda were being identified. They sought to understand how gender roles in piggery systems would dictate whether they interviewed men or women and what questions they would ask.

In preparing research tools, including the questionnaire, the team included questions on participants’ demographic profiles (gender and age) and on how the economic burden of disease is shared among men and women.

A pork joint in Kampala, Uganda in February 2020 (photo credit: ILRI/ K. Dhanji - for the More Pork project of the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock).

Step 3: Prioritize the intervention to investigate and which one to test

The study recommends using a situational analysis to know what interventions to investigate.

The research team noted that, in Uganda, eating outside the home in pork joints was a risk factor for eating undercooked pork, which can lead to infections, a practice that was more common for men than women in many communities. ‘When clients pressure restaurants to hurry with the food, the restaurants may undercook the pork, which can lead to cases of infection,’ Campbell said.

Step 4: Frame recommendations

Campbell called on researchers to exercise a duty of care; a responsibility to minimize harm. In biomedical research, for instance, a lack of gender considerations has had population-wide consequences: women experience more adverse drug reactions. ‘Researchers are part of the mechanism that yields equity, and in applied research, gender can mean solutions that may not serve the unique needs of women and men,’ she said:

Gender affects access to healthcare for the humans and the animals they tend because women who are on the lower ladder socio-economically may not have access to veterinary services like improved pig husbandry or medicine. Therefore, health intervention strategies need to consider ways to reach and serve everyone including women and men and their preferences.

Salome Bukachi is a professor of Anthropology at the Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies, (IAGAS) University of Nairobi and the lead multiplier of COHESA Kenya; Verah Okeyo is an Anthropology PhD Student at the IAGAS, University of Nairobi.

The webinars are a collaboration between The Journal Club at KAVI-ICR, Dept of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Nairobi, led by Prof. Marianne W. Mureithi and the Capacitation One Health in Eastern and Southern Africa (COHESA) project Kenya Team. The project ‘Capacitating One Health in Eastern and Southern Africa (COHESA)’ is co-funded by the OACPSResearch and Innovation Programme, a programme implemented by the Organization of African, Caribbean and Pacific states (OACPS) with the financial support of the European Union